Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Four seasonal coronaviruses—2 of which are betacoronaviruses, like SARS-CoV-2—cause about 30% of common colds. Instead of helping to fight off COVID-19, antibodies to these pathogens may interfere with the SARS-CoV-2 immune response, a recent study of health care workers suggests. Although these preexisting antibodies are ubiquitous, individuals’ varying levels of them might factor into the broad spectrum of responses to the novel coronavirus, which range from immunity against infection all the way to severe respiratory distress and death. Almost since the COVID-19 pandemic began, scientists have investigated how immunity to the seasonal coronaviruses might influence infections with SARS-CoV-2, a new but related virus. A number of reports now show that preexisting common cold coronavirus antibodies are active in SARS-CoV-2 infections, according to Patrick Wilson, PhD, a professor of pediatrics and a scientist in the Gale and Ira Drukier Institute for Children’s Health at Weill Cornell Medicine, who was not involved with the new study. Last year, Wilson and colleagues at the University of Chicago, where he was based at the time, found that people with severe acute SARS-CoV-2 infections had substantial numbers of antibody–secreting B cells that reacted to common cold coronaviruses. The cells had highly mutated and variable genes, likely indicating that they predated the patients’ novel coronavirus infections. As for an influence on COVID-19, one early 2021 University of Pennsylvania study concluded that preexisting antibodies to common cold coronaviruses did not correlate with SARS-CoV-2 protection. But the overall findings have been inconsistent. Taken together, it’s hard to say which way they lean because the studies’ scope, participants, and methods have varied, according to Maureen McGargill, PhD, the senior author of the recent health care workers study and an associate faculty member in immunology at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital, where the research took place. “Keeping these caveats in mind, there were seven reports that concluded high levels of common coronavirus immunity was beneficial, while four reported that it was detrimental, and three reported that it did not have an impact,” McGargill wrote in an email to JAMA. In her study, published in Cell Host & Microbe this January, she and St Jude colleagues investigated whether different levels of preexisting immunity to common cold coronaviruses influenced the likelihood of becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2 or accounted for diverse outcomes following infection. “This is important to study as we still do not understand why some individuals are more susceptible than others to SARS-CoV-2 infection,” she explained.... Published in JAMA (Jan. 26, 2022): https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.0326

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

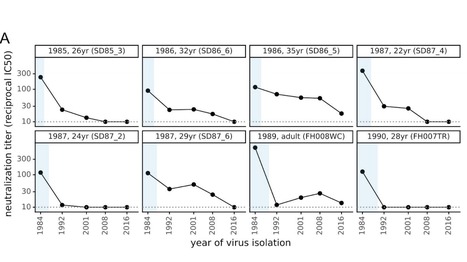

There is intense interest in antibody immunity to coronaviruses. However, it is unknown if coronaviruses evolve to escape such immunity, and if so, how rapidly. Here we address this question by characterizing the historical evolution of human coronavirus 229E. We identify human sera from the 1980s and 1990s that have neutralizing titers against contemporaneous 229E that are comparable to the anti-SARS-CoV-2 titers induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination. We test these sera against 229E strains isolated after sera collection, and find that neutralizing titers are lower against these "future" viruses. In some cases, sera that neutralize contemporaneous 229E viral strains with titers >1:100 do not detectably neutralize strains isolated 8-17 years later. The decreased neutralization of "future" viruses is due to antigenic evolution of the viral spike, especially in the receptor-binding domain. If these results extrapolate to other coronaviruses, then it may be advisable to periodically update SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Preprint available in bioRxiV (Dec. 18, 2020): https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.17.423313

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

T cell reactivity against SARS-CoV-2 was observed in unexposed people; however, the source and clinical relevance of the reactivity remains unknown. It is speculated that this reflects T cell memory to circulating ‘common cold’ coronaviruses. It will be important to define specificities of these T cells and assess their association with COVID-19 disease severity and vaccine responses. Recent studies have shown T cell reactivity to SARS-CoV-2 in 20–50% of unexposed individuals; it is speculated that this is due to T cell memory to common cold coronaviruses. Here, Crotty and Sette discuss the potential implications of these findings for disease severity, herd immunity and vaccine development.... Original review Published in Nature (July 7, 2020): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-020-0389-z

|

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

The Omicron variant of the virus that causes COVID-19 likely acquired at least one of its mutations by picking up a snippet of genetic material from another virus - possibly one that causes the common cold - present in the same infected cells, according to researchers. This genetic sequence does not appear in any earlier versions of the coronavirus, called SARS-CoV-2, but is ubiquitous in many other viruses including those that cause the common cold, and also in the human genome, researchers said. By inserting this particular snippet into itself, Omicron might be making itself look "more human," which would help it evade attack by the human immune system, said Venky Soundararajan of Cambridge, Massachusetts-based data analytics firm nference, who led the study posted on Thursday on the website OSF Preprints. This could mean the virus transmits more easily, while only causing mild or asymptomatic disease. Scientists do not yet know whether Omicron is more infectious than other variants, whether it causes more severe disease or whether it will overtake Delta as the most prevalent variant. It may take several weeks to get answers to these questions. Cells in the lungs and in the gastrointestinal system can harbor SARS-CoV-2 and common-cold coronaviruses simultaneously, according to earlier studies. Such co-infection sets the scene for viral recombination, a process in which two different viruses in the same host cell interact while making copies of themselves, generating new copies that have some genetic material from both "parents." This new mutation could have first occurred in a person infected with both pathogens when a version of SARS-CoV-2 picked up the genetic sequence from the other virus, Soundararajan and colleagues said in the study, which has not yet been peer-reviewed. The same genetic sequence appears many times in one of the coronaviruses that causes colds in people - known as HCoV-229E - and in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) that causes AIDS, Soundararajan said. South Africa, where Omicron was first identified, has the world's highest rate of HIV, which weakens the immune system and increases a person's vulnerability to infections with common-cold viruses and other pathogens. In that part of the world, there are many people in whom the recombination that added this ubiquitous set of genes to Omicron might have occurred, Soundararajan said. "We probably missed many generations of recombinations" that occurred over time and that led to the emergence of Omicron, Soundararajan added. More research is needed to confirm the origins of Omicron's mutations and their effects on function and transmissibility. There are competing hypotheses that the latest variant might have spent some time evolving in an animal host. In the meantime, Soundararajan said, the new findings underscore the importance of people getting the currently available COVID-19 vaccines. "You have to vaccinate to reduce the odds that other people, who are immunocompromised, will encounter the SARS-CoV-2 virus," Soundararajan said. Preprint with original findings available in OSFPreprints (Dec. 2, 2021): https://osf.io/f7txy/

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

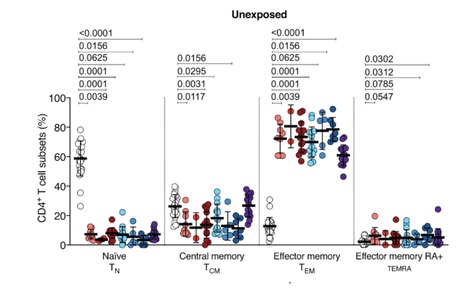

Many unknowns exist about human immune responses to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. SARS-CoV-2 reactive CD4+ T cells have been reported in unexposed individuals, suggesting pre-existing cross-reactive T cell memory in 20-50% of people. However, the source of those T cells has been speculative. Using human blood samples derived before the SARS-CoV-2 virus was discovered in 2019, we mapped 142 T cell epitopes across the SARS-CoV-2 genome to facilitate precise interrogation of the SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4+ T cell repertoire. We demonstrate a range of pre-existing memory CD4+ T cells that are cross-reactive with comparable affinity to SARS-CoV-2 and the common cold coronaviruses HCoV-OC43, HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63, or HCoV-HKU1. Thus, variegated T cell memory to coronaviruses that cause the common cold may underlie at least some of the extensive heterogeneity observed in COVID-19 disease. Published in Science (August 4, 2020): https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd3871

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

On January 9 of this year, Chinese state media reported that a team of researchers led by Xu Jianguo had identified the pathogen behind a mysterious outbreak of pneumonia in Wuhan as a novel coronavirus. Although the virus was soon after named 2019-nCoV, and then renamed SARS-CoV-2, it remains commonly known simply as the coronavirus. While that moniker has been catapulted into the stratosphere of public attention, it’s somewhat misleading: Not only is it one of many coronaviruses out there, but you’ve almost certainly been infected with members of the family long before SARS-CoV-2’s emergence in late 2019. Coronaviruses take their name from the distinctive spikes with rounded tips that decorate their surface, which reminded virologists of the appearance of the sun’s atmosphere, known as its corona. Various coronaviruses infect numerous species, but the first human coronaviruses weren’t discovered until the mid-1960s. “That was sort of the golden days, if you will, of virology, because at that time the technology became available to grow viruses in the laboratory, and to study viruses in the laboratory,” says University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center pediatrician Jeffrey Kahn, who studies respiratory viruses. But the two coronaviruses that were identified at the time, OC43 and 229E, didn’t elicit much research interest, says Kahn, who wrote a review on coronaviruses a few years after the SARS outbreak of 2003. “I don't believe there was a big effort to make vaccines against these because these were thought to be more of a nuisance than anything else.” The viruses cause typical cold symptoms such as a sore throat, cough, and stuffy nose, and they seemed to be very common; one early study estimated that 3 percent of respiratory illnesses in a children’s home in Georgia over seven years in the 1960s had been caused by OC43, and a 1986 study of children and adults in northern Italy found that it was rare to come across a subject who did not have antibodies to that virus (an indicator of past infection)......

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...