Bird flu is infecting the brains of wild mammals such as foxes and raccoons and may be making them behave in unusual ways, according to a study in the US. Out of 57 live mammals found to be infected, 53 had neurological symptoms, such as seizures, problems with balance, tremors and a lack of fear of people. The risk to people appears to be low. “There isn’t yet any evidence that red foxes or other wild mammals …

Get Started for FREE

Sign up with Facebook Sign up with X

I don't have a Facebook or a X account

Your new post is loading... Your new post is loading...

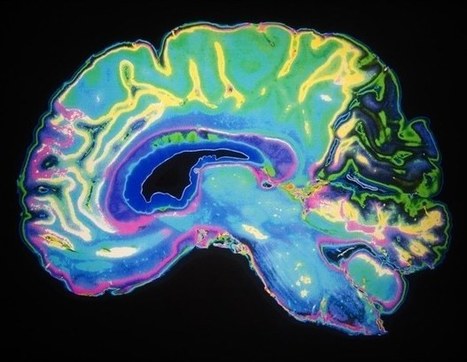

SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19 infects and replicates in astrocytes, reducing neural viability. A preliminary version (not yet peer-reviewed) posted in 2020 was one of the first to show that the virus that causes COVID-19 can infect brain cells, especially astrocytes. It also broke new ground by describing alterations in the structure of the cortex, the most neuron-rich brain region, even in cases of mild COVID-19. The cerebral cortex is the outer layer of gray matter over the hemispheres. It is the largest site of neural integration in the central nervous system and plays a key role in complex functions such as memory, attention, consciousness, and language. The investigation was conducted by several groups at the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP) and the University of São Paulo (USP). Researchers at the Brazilian Biosciences National Laboratory (LNBio), D’Or Institute (IDOR) and the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) also contributed to the study. “Two previous studies detected the presence of the novel coronavirus in the brain, but no one knew for sure if it was in the bloodstream, endothelial cells [lining the blood vessels] or nerve cells. We showed for the first time that it does indeed infect and replicate in astrocytes, and that this can reduce neuron viability,” Daniel Martins-de-Souza, one of the leaders of the study, told Agência FAPESP. Martins-de-Souza is a professor at UNICAMP’s Biology Institute and a researcher affiliated with IDOR. Astrocytes are the most abundant central nervous system cells. Their functions include providing biochemical support and nutrients for neurons; regulating levels of neurotransmitters and other substances that may interfere with neuronal functioning, such as potassium; maintaining the blood-brain barrier that protects the brain from pathogens and toxins; and helping to maintain brain homeostasis. Infection of astrocytes was confirmed by experiments using brain tissue from 26 patients who died of COVID-19. The tissue samples were collected during autopsies conducted using minimally invasive procedures by Alexandre Fabro, a pathologist and professor at the University of São Paulo’s Ribeirão Preto Medical School (FMRP-USP). The analysis was coordinated by Thiago Cunha, also a professor in FMRP-USP and a member of the Center for Research on Inflammatory Diseases (CRID).

The researchers used a technique known as immunohistochemistry, a staining process in which antibodies act as markers of viral antigens or other components of the tissue analyzed. “For example, we can insert one antibody into the sample to turn the astrocytes red on binding to them, another to mark the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein by making it green, and a third to highlight the virus’s double-stranded RNA, which only appears during replication, by turning it magenta,” Martins-de-Souza explained. “When the images produced during the experiment were overlaid, all three colors appeared simultaneously only in astrocytes.” According to Cunha, the presence of the virus was confirmed in five of the 26 samples analyzed. Alterations suggesting possible damage to the central nervous system were also found in these five samples. “We observed signs of necrosis and inflammation, such as edema [swelling caused by a buildup of fluid], neuronal lesions and inflammatory cell infiltrates,” he said. The capacity of SARS-CoV-2 to infect brain tissue and its preference for astrocytes were confirmed by Adriano Sebolella and his group at FMRP-USP using the method of brain-derived slice cultures, an experimental model in which human brain tissue obtained during surgery to treat neurological diseases such as drug-refractory epilepsy, for example, is cultured in vitro and infected with the virus.

Persistent symptoms In another part of the research, conducted in UNICAMP’s School of Medical Sciences (FCM), 81 volunteers who had recovered from mild COVID-19 were submitted to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of their brains. These scans were performed 60 days after diagnostic testing on average. A third of the participants still had neurological or neuropsychiatric symptoms at the time. They complained mostly of headache (40%), fatigue (40%), memory alterations (30%), anxiety (28%), loss of smell (28%), depression (20%), daytime drowsiness (25%), loss of taste (16%) and low libido (14%). “We posted a link for people interested in participating in the trial to register, and were surprised to get more than 200 volunteers in only a few days. Many were polysymptomatic, with widely varying complaints. In addition to the neuroimaging exam, they’re being evaluated neurologically and taking standardized tests to measure performance in cognitive functions such as memory, attention and mental flexibility. In the article we present the initial results,” said Clarissa Yasuda, a professor and member of the Brazilian Research Institute for Neuroscience and Neurotechnology (BRAINN). Only volunteers diagnosed with COVID-19 by RT-PCR and not hospitalized were included in the study. The assessments were carried out after the end of the acute phase, and the results were compared with data for 145 healthy uninfected subjects. The MRI scans showed that some volunteers had decreased cortical thickness in some brain regions compared with the average for controls.

“We observed atrophy in areas associated, for example with anxiety, one of the most frequent symptoms in the study group,” Yasuda said. “Considering that the prevalence of anxiety disorders in the Brazilian population is 9%, the 28% we found is an alarmingly high number. We didn’t expect these results in patients who had had the mild form of the disease.” In neuropsychological tests designed to evaluate cognitive functioning, the volunteers also underperformed in some tasks compared with the national average. The results were adjusted for age, sex and educational attainment, as well as the degree of fatigue reported by each participant. “The question we’re left with is this: Are these symptoms temporary or permanent? So far, we’ve found that some subjects improve, but unfortunately many continue to experience alterations,” Yasuda said. “What’s surprising is that many people have been reinfected by novel variants, and some report worse symptoms than they had since the first infection. In view of the novel virus, we see longitudinal follow-up as crucial to understand the evolution of the neuropsychiatric alterations over time and for this understanding to serve as a basis for the development of targeted therapies.”

Energy metabolism affected In IB-UNICAMP’s Neuroproteomics Laboratory, which is headed by Martins-de-Souza, experiments were performed on brain tissue cells from people who died of COVID-19 and astrocytes cultured in vitro to find out how infection by SARS-CoV-2 affects nervous system cells from the biochemical standpoint. The autopsy samples were obtained via collaboration with the group led by Paulo Saldiva, a professor at the University of São Paulo’s Medical School (FM-USP). The proteome (all proteins present in the tissue) was mapped using mass spectrometry, a technique employed to identify different substances in biological samples according to their molecular mass. “When the results were compared with those of uninfected subjects, several proteins with altered expression were found to be abundant in astrocytes, which validated the findings obtained by immunohistochemistry,” Martins-de-Souza said. “We observed alterations in various biochemical pathways in the astrocytes, especially pathways associated with energy metabolism.” The next step was to repeat the proteomic analysis in cultured astrocytes infected in the laboratory. The astrocytes were obtained from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). The method consists of reprogramming adult cells (derived from skin or other easily accessible tissues) to assume a stage of pluripotency similar to that of embryo stem cells.

This first part was conducted in the IDOR laboratory of Stevens Rehen, a professor at UFRJ. Martins-de-Souza’s team then used chemical stimuli to make the iPSCs differentiate into neural stem cells and eventually into astrocytes. “The results were similar to those of the analysis of tissue samples obtained by autopsy in that they showed energy metabolism dysfunction,” Martins-de-Souza said. “We then performed a metabolomic analysis [focusing on the metabolites produced by the cultured astrocytes], which evidenced glucose metabolism alterations. For some reason, infected astrocytes consume more glucose than usual, and yet cellular levels of pyruvate and lactate, the main energy substrates, decreased significantly.” Lactate is one of the products of glucose metabolism, and astrocytes export this metabolite to neurons, which use it as an energy source. The researchers’ in vitro analysis showed that lactate levels in the cell culture medium were normal but decreased inside the cells. “Astrocytes appear to strive to maintain the energy supply to neurons even if this effort weakens their own functioning,” Martins-de-Souza said. As an outcome of this process, the functioning of the astrocytes’ mitochondria (energy-producing organelles) was indeed altered, potentially influencing cerebral levels of such neurotransmitters as glutamate, which excites neurons and is associated with memory and learning, or gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which inhibits excessive firing of neurons and can promote feelings of calm and relaxation.

“In another experiment, we attempted to culture neurons in the medium where the infected astrocytes had grown previously and measured a higher-than-expected cell death rate. In other words, this culture medium ‘conditioned by infected astrocytes’ weakened neuron viability,” Martins-de-Souza said. The findings described in the article confirm those of several previously published studies pointing to possible neurological and neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID-19. Results of experiments on hamsters conducted at the Institute of Biosciences (IB-USP), for example, reinforce the hypothesis that infection by SARS-CoV-2 accelerates astrocyte metabolism and increases the consumption of molecules used to generate energy, such as glucose and the amino acid glutamine. The results obtained by the group led by Jean Pierre Peron indicate that this metabolic alteration impairs the synthesis of a neurotransmitter that plays a key role in communication among neurons.

Unanswered questions According to Martins-de-Souza, there is no consensus in the scientific literature on how SARS-CoV-2 reaches the brain. “Some animal experiments suggest the virus can cross the blood-brain barrier. There’s also a suspicion that it infects the olfactory nerve and from there invades the central nervous system. But these are hypotheses for now,” he said. One of the discoveries revealed by the PNAS article is that the virus does not use the protein ACE-2 to invade central nervous system cells, as it does in the lungs. “Astrocytes don’t have the protein in their membranes. Research by Flávio Veras [FMRP-USP] and his group shows that SARS-CoV-2 binds to the protein neuropilin in this case, illustrating its versatility in infecting different tissues,” Martins-de-Souza said. At UNICAMP’s Neuroproteomics Laboratory, Martins-de-Souza analyzed nerve cells and others affected by COVID-19, such as adipocytes, immune system cells and gastrointestinal cells, to see how the infection altered the proteome. “We’re now compiling the data to look for peculiarities and differences in the alterations caused by the virus in these different tissues. Thousands of proteins and hundreds of biochemical pathways can be altered, with variations in each case. This knowledge will help guide the search for specific therapies for each system impaired by COVID-19,” he said. “We’re also comparing the proteomic differences observed in brain tissue from patients who died of COVID-19 with proteomic differences we’ve found over the years in patients with schizophrenia. The symptoms of both conditions are quite similar. Psychosis, the most classic sign of schizophrenia, also occurs in people with COVID-19.” The aim of the study is to find out whether infection by SARS-CoV-2 can lead to degeneration of the white matter in the brain, made up mainly of glial cells (astrocytes and microglia) and axons (extensions of neurons). “We’ve observed a significant correspondence [in the pattern of proteomic alterations] associated with the energy metabolism and glial proteins that appear important in both COVID-19 and schizophrenia. These findings may perhaps provide a shortcut to treatments for the psychiatric symptoms of COVID-19,” Martins-de-Souza pondered. Marcelo Mori, a professor at IB-UNICAMP and a member of the Obesity and Comorbidities Research Center (OCRC), the study was only possible thanks to the collaboration of researchers with varied and complementary backgrounds and expertise. “It demonstrates that first-class competitive science is always interdisciplinary,” he said. “It’s hard to compete internationally if you stay inside your own lab, confining yourself to the techniques with which you’re familiar and the equipment to which you have access.”

Neurological symptoms in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients have been reported, but their cause remains unclear. In theory, the neurological symptoms observed after SARS-CoV-2 infection could be (i) directly caused by the virus infecting brain cells, (ii) indirectly by our body’s local or systemic immune response towards the virus, (iii) by co-incidental phenomena or (iv) a combination of these factors. As indisputable evidence of intact and replicating SARS-CoV-2 particles in the central nervous system (CNS) is currently lacking, we suggest focusing on the host’s immune reaction when trying to understand the neurocognitive symptoms associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. In this Perspective, we discuss the possible immune-mediated mechanisms causing functional or structural CNS alterations during acute infection as well as in the post-infectious context. We also review the available literature on CNS affection in the context of COVID-19 infection, as well as observations from animal studies on the molecular pathways involved in sickness behavior. Published in Immunity June (19, 2022):

The hospitalized patients showed signs of deteriorating neurological function, ranging from confusion to coma-like unresponsiveness, new research indicates. Nearly a third of hospitalized Covid-19 patients experienced some type of altered mental function — ranging from confusion to delirium to unresponsiveness — in the largest study to date of neurological symptoms among coronavirus patients in an American hospital system. And patients with altered mental function had significantly worse medical outcomes, according to the study, published on Monday in Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology. The study looked at the records of the first 509 coronavirus patients hospitalized, from March 5 to April 6, at 10 hospitals in the Northwestern Medicine health system in the Chicago area. These patients stayed three times as long in the hospital as patients without altered mental function. After they were discharged, only 32 percent of the patients with altered mental function were able to handle routine daily activities like cooking and paying bills, said Dr. Igor Koralnik, the senior author of the study and chief of neuro-infectious disease and global neurology at Northwestern Medicine. In contrast, 89 percent of patients without altered mental function were able to manage such activities without assistance.

Patients with altered mental function — the medical term is encephalopathy — were also nearly seven times as likely to die as those who did not have that type of problem. “Encephalopathy is a generic term meaning something’s wrong with the brain,” Dr. Koralnik said. The description can include problems with attention and concentration, loss of short-term memory, disorientation, stupor and “profound unresponsiveness” or a coma-like level of consciousness. “Encephalopathy was associated with the worst clinical outcomes in terms of ability to take care of their own affairs after leaving the hospital, and we also see it’s associated with higher mortality, independent of severity of their respiratory disease,” he said. The researchers did not identify a cause for the encephalopathy, which can occur with other diseases, especially in older patients, and can be triggered by several different factors including inflammation and effects on blood circulation, said Dr. Koralnik, who also oversees the Neuro Covid-19 Clinic at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. There is very little evidence so far that the virus directly attacks brain cells, and most experts say neurological effects are probably triggered by inflammatory and immune system responses that often affect other organs, as well as the brain.

“This paper indicates, importantly, that in-hospital encephalopathy may be a predictor for poorer outcomes,” said Dr. Serena Spudich, chief of neurological infections and global neurology at Yale School of Medicine, who was not involved in the study. That finding would also suggest that patients with altered mental function in the hospital “might benefit from closer post-discharge monitoring or rehabilitation,” she added. In the study, the 162 patients with encephalopathy were more likely to be older and male. They were also more likely to have underlying medical conditions, including a history of any neurological disorder, cancer, cerebrovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, high cholesterol, heart failure, hypertension or smoking. Some experts said that President Trump, who was hospitalized with Covid at Walter Reed military hospital beginning on Friday, is of the age and gender of the patients in the study who were more likely to develop altered mental function and therefore could be at higher risk for such symptoms. He also has a history of high cholesterol, one of the pre-existing conditions that appear to increase risk. But the president’s doctors have given no indication that he has had any neurological symptoms; the White House had released videos of him talking to the public about how well he was doing. And Mr. Trump returned to the White House on Monday evening....

Study published in Annals Clinica and Translational Neurology (October 5, 2020):

As if the symptoms of COVID-19 were not disturbing enough, physicians have noted a rare neurological condition that emerges during some severe cases of this viral infection. The patient in the case report (let’s call him Tom) was 54 and in good health. For two days in May, he felt unwell and was too weak to get out of bed. When his family finally brought him to the hospital, doctors found that he had a fever and signs of a severe infection, or sepsis. He tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 infection. In addition to symptoms of COVID-19, he was also too weak to move his legs. When a neurologist examined him, Tom was diagnosed with Guillain-Barre Syndrome, an autoimmune disease that causes abnormal sensation and weakness due to delays in sending signals through the nerves. Usually reversible, in severe cases it can cause prolonged paralysis involving breathing muscles, require ventilator support and sometimes leave permanent neurological deficits. Early recognition by expert neurologists is key to proper treatment.

We are neurologists specializing in intensive care and leading studies related to neurological complications from COVID-19. Given the occurrence of Guillain-Barre Syndrome in prior pandemics with other corona viruses like SARS and MERS, we are investigating a possible link between Guillain-Barre Syndrome and COVID-19 and tracking published reports to see if there is any link between Guillain-Barre Syndrome and COVID-19. Some patients may not seek timely medical care for neurological symptoms like prolonged headache, vision loss and new muscle weakness due to fear of getting exposed to virus in the emergency setting. People need to know that medical facilities have taken full precautions to protect patients. Seeking timely medical evaluation for neurological symptoms can help treat many of these diseases.

Guillain-Barre syndrome occurs when the body’s own immune system attacks and injures the nerves outside of the spinal cord or brain – the peripheral nervous system. Most commonly, the injury involves the protective sheath, or myelin, that wraps nerves and is essential to nerve function. Without the myelin sheath, signals that go through a nerve are slowed or lost, which causes the nerve to malfunction...

Marine Degroise's curator insight,

October 17, 2022 9:39 AM

Cas témoin d'un patient, ayant eu la Covid 19 suivi d'un syndrome de Guillain Barré, on se demande donc s'il peut avoir un lien entre ces 2 maladies. D'après nos connaissances le syndrome de Guillain-Barré peut survenir après une infection comme la grippe ou plein d'autre, il est donc fortement probable que la Covid-19 puisse engendrer un Guillain Barré.

The symptoms suggest SARS-CoV-2 might infect neurons, raising questions about whether there could be effects on the brain that play a role in patients’ deaths, but the data are preliminary. Nearly two weeks ago, Alessandro Laurenzi, a biologist working as a consultant in Bologna, Italy, was mowing the grass in his garden when a friend stopped him and said the mower reeked of fuel. “I couldn’t smell anything at all,” he tells The Scientist. That was in the morning. A few hours later, he went to have lunch and realized he couldn’t smell the food he was about to eat and when he took a bite, he couldn’t taste it either. Within a few days, he developed symptoms of COVID-19 and called his doctor to ask if he could get tested. Because his symptoms were mild, Laurenzi says, his doctor said no. Laurenzi had heard anecdotally that many COVID-19 patients in Italy suffered from a loss of smell, so he started reading all the scientific papers he could find to see if his anosmia and ageusia would ever abate. One of the papers, a review published March 13, mentioned that SARS-CoV-2, like other coronaviruses such as SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, could target the central nervous system, possibly infecting neurons in the nasal passage and disrupting the senses of smell and taste.

Reading this, Laurenzi immediately reached out to the corresponding author, Abdul Mannan Baig, a researcher at Aga Khan University in Pakistan, and asked if his symptoms were reversible. The evidence, Mannan told Laurenzi and reiterated to The Scientist, indicates they will abate, possibly because the loss of sense is caused by inflammation in the area as the body fights the virus, so those symptoms could disappear in seven to 14 days. “Let’s hope so,” Laurenzi tells The Scientist. Documenting such peculiar symptoms is important, Mannan tells The Scientist, because the loss of smell and taste could be an early warning sign of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Based on the literature, British ear, nose, and throat doctors have now called for adults who lost those senses to quarantine themselves in an attempt to tamp down the spread of the disease, The New York Times reports. The symptoms, Mannan adds, also suggest that the virus has the ability to invade the central nervous system, which could cause neurological damage and possibly play a role in patients dying from COVID-19. |

Growing evidence links COVID-19 with acute and long-term neurological dysfunction. However, the pathophysiological mechanisms resulting in central nervous system involvement remain unclear, posing both diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Here we show outcomes of a cross-sectional clinical study (NCT04472013) including clinical and imaging data and corresponding multidimensional characterization of immune mediators in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and plasma of patients belonging to different Neuro-COVID severity classes. The most prominent signs of severe Neuro-COVID are blood-brain barrier (BBB) impairment, elevated microglia activation markers and a polyclonal B cell response targeting self-antigens and non-self-antigens. COVID-19 patients show decreased regional brain volumes associating with specific CSF parameters, however, COVID-19 patients characterized by plasma cytokine storm are presenting with a non-inflammatory CSF profile. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome strongly associates with a distinctive set of CSF and plasma mediators. Collectively, we identify several potentially actionable targets to prevent or intervene with the neurological consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Both acute and chronic COVID-19 disease (also known as long-COVID) may affect the central nervous system. Here authors characterize the immunological profile of peripheral blood and cerebrospinal fluid of COVID-19 patients in order to identify the main factors that contribute to neurological impairment and the severity of neurological symptoms in Sars-CoV-2 infection.

Published in Nature Communications (Nov. 09, 2022): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34068-0

If you've had COVID-19, it may still be messing with your brain. Those who have been infected with the virus are at increased risk of developing a range of neurological conditions in the first year after the infection, new research shows. Such complications include strokes, cognitive and memory problems, depression, anxiety and migraine headaches, according to a comprehensive analysis of federal health data by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care system. Additionally, the post-COVID brain is associated with movement disorders, from tremors and involuntary muscle contractions to epileptic seizures, hearing and vision abnormalities, and balance and coordination difficulties as well as other symptoms similar to what is experienced with Parkinson's disease. The findings are published Sept. 22 in Nature Medicine. Overall, COVID-19 has contributed to more than 40 million new cases of neurological disorders worldwide, Al-Aly said. Other than having a COVID infection, specific risk factors for long-term neurological problems are scarce. "We're seeing brain problems in previously healthy individuals and those who have had mild infections," Al-Aly said. "It doesn't matter if you are young or old, female or male, or what your race is. It doesn't matter if you smoked or not, or if you had other unhealthy habits or conditions."

Few people in the study were vaccinated for COVID-19 because the vaccines were not yet widely available during the time span of the study, from March 2020 through early January 2021. The data also predates delta, omicron and other COVID variants. A previous study in Nature Medicine led by Al-Aly found that vaccines slightly reduce -; by about 20% -; the risk of long-term brain problems. "It is definitely important to get vaccinated but also important to understand that they do not offer complete protection against these long-term neurologic disorders," Al-Aly said. The researchers analyzed about 14 million de-identified medical records in a database maintained by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the nation's largest integrated health-care system. Patients included all ages, races and sexes. They created a controlled data set of 154,000 people who had tested positive for COVID-19 sometime from March 1, 2020, through Jan. 15, 2021, and who had survived the first 30 days after infection. Statistical modeling was used to compare neurological outcomes in the COVID-19 data set with two other groups of people not infected with the virus: a control group of more than 5.6 million patients who did not have COVID-19 during the same time frame; and a control group of more than 5.8 million people from March 2018 to December 31, 2019, long before the virus infected and killed millions across the globe.

The researchers examined brain health over a year-long period. Neurological conditions occurred in 7% more people with COVID-19 compared with those who had not been infected with the virus. Extrapolating this percentage based on the number of COVID-19 cases in the U.S., that translates to roughly 6.6 million people who have suffered brain impairments associated with the virus. Memory problems -; colloquially called brain fog -; are one of the most common brain-related, long-COVID symptoms. Compared with those in the control groups, people who contracted the virus were at a 77% increased risk of developing memory problems. "These problems resolve in some people but persist in many others," Al-Aly said. "At this point, the proportion of people who get better versus those with long-lasting problems is unknown." Interestingly, the researchers noted an increased risk of Alzheimer's disease among those infected with the virus. There were two more cases of Alzheimer's per 1,000 people with COVID-19 compared with the control groups. "It's unlikely that someone who has had COVID-19 will just get Alzheimer's out of the blue," Al-Aly said. "Alzheimer's takes years to manifest. But what we suspect is happening is that people who have a predisposition to Alzheimer's may be pushed over the edge by COVID, meaning they're on a faster track to develop the disease. It's rare but concerning." Also compared to the control groups, people who had the virus were 50% more likely to suffer from an ischemic stroke, which strikes when a blood clot or other obstruction blocks an artery's ability to supply blood and oxygen to the brain. Ischemic strokes account for the majority of all strokes, and can lead to difficulty speaking, cognitive confusion, vision problems, the loss of feeling on one side of the body, permanent brain damage, paralysis and death.

"There have been several studies by other researchers that have shown, in mice and humans, that SARS-CoV-2 can attack the lining of the blood vessels and then then trigger a stroke or seizure," Al-Aly said. "It helps explain how someone with no risk factors could suddenly have a stroke." Overall, compared to the uninfected, people who had COVID-19 were 80% more likely to suffer from epilepsy or seizures, 43% more likely to develop mental health disorders such as anxiety or depression, 35% more likely to experience mild to severe headaches, and 42% more likely to encounter movement disorders. The latter includes involuntary muscle contractions, tremors and other Parkinson's-like symptoms. COVID-19 sufferers were also 30% more likely to have eye problems such as blurred vision, dryness and retinal inflammation; and they were 22% more likely to develop hearing abnormalities such as tinnitus, or ringing in the ears. "Our study adds to this growing body of evidence by providing a comprehensive account of the neurologic consequences of COVID-19 one year after infection," Al-Aly said. Long COVID's effects on the brain and other systems emphasize the need for governments and health systems to develop policy, and public health and prevention strategies to manage the ongoing pandemic and devise plans for a post-COVID world, Al-Aly said. "Given the colossal scale of the pandemic, meeting these challenges requires urgent and coordinated -; but, so far, absent -; global, national and regional response strategies," he said.

Cited research published in Nature Medicine (Sept. 22, 2022): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02001-z

Of the more than 16,000 patients examined, 13% developed serious neurological conditions including, most commonly, encephalopathy at admission. A peer-reviewed study published in April in the journal Critical Care Explorations found a correlation between neurological conditions and the severity of COVID-19 symptoms. It has already been documented that people with pre-existing conditions affecting the cardiovascular or immune systems are more likely to become seriously ill or hospitalized when contracting COVID-19. This new international study examined otherwise healthy patients who have developed neurological impairments after being admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of COVID-19. Of the more than 16,000 patients examined, 13% developed serious neurological conditions including, most commonly, encephalopathy upon admission. Encephalopathy is an umbrella term for brain disease or damage that causes a marked change in the way the brain works, or how the brain and body interact.

Researchers also observed stroke and seizure, as well as meningitis/encephalitis which are both characterized by inflammation of or around the brain, and were counted in the same category. All of these neurological manifestations were much less common than encephalitis and were associated with increased ICU support needs and more severe disease in general. “Given the association of neurologic manifestations with poorer outcomes," concluded the study's author, Dr. Anna Cervantes-Arslanian, "further study is desperately needed to understand why these differences occur and what can be done to intervene."

Published April 2022 in the Journal of Critical Care Explorations:

It’s not just the lungs — the pathogen may enter brain cells, causing symptoms like delirium and confusion, scientists reported. The coronavirus targets the lungs foremost, but also the kidneys, liver and blood vessels. Still, about half of patients report neurological symptoms, including headaches, confusion and delirium, suggesting the virus may also attack the brain. A new study offers the first clear evidence that, in some people, the coronavirus invades brain cells, hijacking them to make copies of itself. The virus also seems to suck up all of the oxygen nearby, starving neighboring cells to death. It’s unclear how the virus gets to the brain or how often it sets off this trail of destruction. Infection of the brain is likely to be rare, but some people may be susceptible because of their genetic backgrounds, a high viral load or other reasons. “If the brain does become infected, it could have a lethal consequence,” said Akiko Iwasaki, an immunologist at Yale University who led the work. The study was posted online on Wednesday and has not yet been vetted by experts for publication. But several researchers said it was careful and elegant, showing in multiple ways that the virus can infect brain cells.

Scientists have had to rely on brain imaging and patient symptoms to infer effects on the brain, but “we hadn’t really seen much evidence that the virus can infect the brain, even though we knew it was a potential possibility,” said Dr. Michael Zandi, consultant neurologist at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in Britain. “This data just provides a little bit more evidence that it certainly can.” Dr. Zandi and his colleagues published research in July showing that some patients with Covid-19, the illness caused by the coronavirus, develop serious neurological complications, including nerve damage. In the new study, Dr. Iwasaki and her colleagues documented brain infection in three ways: in brain tissue from a person who died of Covid-19, in a mouse model and in organoids — clusters of brain cells in a lab dish meant to mimic the brain’s three-dimensional structure.

Other pathogens — including the Zika virus — are known to infect brain cells. Immune cells then flood the damaged sites, trying to cleanse the brain by destroying infected cells. The coronavirus is much stealthier: It exploits the brain cells’ machinery to multiply, but doesn’t destroy them. Instead, it chokes off oxygen to adjacent cells, causing them to wither and die. The researchers didn’t find any evidence of an immune response to remedy this problem. “It’s kind of a silent infection,” Dr. Iwasaki said. “This virus has a lot of evasion mechanisms.” These findings are consistent with other observations in organoids infected with the coronavirus, said Alysson Muotri, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Diego, who has also studied the Zika virus. The coronavirus seems to rapidly decrease the number of synapses, the connections between neurons. “Days after infection, and we already see a dramatic reduction in the amount of synapses,” Dr. Muotri said. “We don’t know yet if that is reversible or not.” The virus infects a cell via a protein on its surface called ACE2. That protein appears throughout the body and especially in the lungs, explaining why they are favored targets of the virus. Previous studies have suggested, based on a proxy for protein levels, that the brain has very little ACE2 and is likely to be spared. But Dr. Iwasaki and her colleagues looked more closely and found that the virus could indeed enter brain cells using this doorway. “It’s pretty clear that it is expressed in the neurons and it’s required for entry,” Dr. Iwasaki said. Her team then looked at two sets of mice — one with the ACE2 receptor expressed only in the brain, and the other with the receptor only in the lungs. When researchers introduced the virus into these mice, the brain-infected mice rapidly lost weight and died within six days. The lung-infected mice did neither...

Preprint of the Study available in bioRxiv (Sept. 8, 2020):

UK neurologists publish details of mildly affected or recovering patients with serious or potentially fatal brain conditions. Doctors may be missing signs of serious and potentially fatal brain disorders triggered by coronavirus, as they emerge in mildly affected or recovering patients, scientists have warned. The cases, published in the journal Brain, revealed a rise in a life-threatening condition called Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis (Adem), as the first wave of infections swept through Britain. At UCL’s Institute of Neurology, Adem cases rose from one a month before the pandemic to two or three per week in April and May. One woman, who was 59, died of the complication.

A dozen patients had inflammation of the central nervous system, 10 had brain disease with delirium or psychosis, eight had strokes and a further eight had peripheral nerve problems, mostly diagnosed as Guillain-Barré syndrome, an immune reaction that attacks the nerves and causes paralysis. It is fatal in 5% of cases. “We’re seeing things in the way Covid-19 affects the brain that we haven’t seen before with other viruses,” said Michael Zandi, a senior author on the study and a consultant at the institute and University College London Hospitals NHS foundation trust. “What we’ve seen with some of these Adem patients, and in other patients, is you can have severe neurology, you can be quite sick, but actually have trivial lung disease,” he added. “Biologically, Adem has some similarities with multiple sclerosis, but it is more severe and usually happens as a one-off. Some patients are left with long-term disability, others can make a good recovery.” The cases add to concerns over the long-term health effects of Covid-19, which have left some patients breathless and fatigued long after they have cleared the virus, and others with numbness, weakness and memory problems...

Original Study Published in Brain (July 8, 2020):

Nassima Chraibi's curator insight,

January 9, 2023 12:01 PM

SRAS-CoV-2 has effects on the brain that are specific to this virus, even long after infection. Thus, the management of patients must be complete, since the effects are diverse and varied.

New UCLA-led research suggests that 32% of children up to the age of 3 years who were exposed to the Zika virus during the mother's pregnancy had below-average neurological development. The study also found that less than 4 percent of 216 children evaluated had microcephaly—a smaller-than-normal head that is one of the hallmarks of the mosquito-borne disease. The heads of two of those children grew to normal size over time, the researchers reported.

The findings, conducted by UCLA researchers with colleagues in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where the disease was first detected, as well as in Austria and Germany, are a follow-up to previous research. That study showed substantial neurologic damage identified through developmental testing and neuroimaging in children younger than age two whose mothers were infected with Zika during their pregnancies.

The researchers tested 146 children using the Bayley-III test, an extended neurodevelopmental assessment that checks language, cognitive and motor development. They used the Hammersmith Infant Neurologic Evaluation, or HINE, a less detailed assessment, on the 70 other children whose parents did not wish to take their children in for the lengthy Bayley-III. The researchers found that in the Bayley-III group, 51 children tested for language, 14 tested for cognitive development, and 24 evaluated for motor development scored below average.

The study was published in Nature Medicine today: |