Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

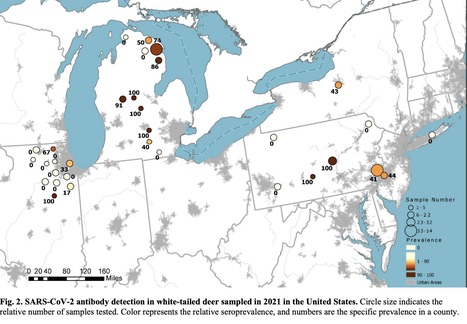

Widespread human SARS-CoV-2 infections combined with human-wildlife interactions create the potential for reverse zoonosis from humans to wildlife. We targeted white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) for serosurveillance based on evidence these deer have ACE2 receptors with high affinity for SARS-CoV-2, are permissive to infection, exhibit sustained viral shedding, can transmit to conspecifics, and can be abundant near urban centers. We evaluated 624 pre- and post-pandemic serum samples from wild deer from four U.S. states for SARS-CoV-2 exposure. Antibodies were detected in 152 samples (40%) from 2021 using a surrogate virus neutralization test. A subset of samples was tested using a SARS-CoV-2 virus neutralization test with high concordance between tests. These data suggest white-tailed deer in the populations assessed have been exposed to SARS-CoV-2. Preprint available in bioRxiv (July 29, 2021): https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.29.454326

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Infected cats and dogs experience serious symptoms, but it’s unclear whether the virus is causing them. The variants of SARS-CoV-2 that keep emerging aren’t just a human problem. Two reports released this week have found the first evidence that dogs and cats can become infected by B.1.1.7, a recent variant of the pandemic coronavirus that transmits more readily between people and also appears more lethal in them. The finds mark the first time one of the several major variants of concern has been seen outside of humans. B.1.1.7 was first identified in the United Kingdom and that’s where some of the variant-infected pets were found. The U.K. animals suffered myocarditis—an inflammation of the heart tissue that, in serious cases, can cause heart failure. But the reports offer no proof that the SARS-CoV-2 variant is responsible, nor that it’s more transmissible or dangerous in animals. “It’s an interesting hypothesis, but there’s no evidence that the virus is causing these problems,” says Scott Weese, a veterinarian at the University of Guelph’s Ontario Veterinary College who specializes in emerging infectious diseases. Since December 2020, scientists have identified multiple variants of concern that appear more transmissible or are able to evade some immune response. B.1.351, for example, was first detected in South Africa, and a strain called P.1 was first found in Brazil. The B.1.1.7 variant drew early attention because of its rapid rise in the United Kingdom; it now comprises about 95% of all new infections there. So far the impact of these variants on pets has been unclear. Though there have now been more than 120 million cases of COVID-19 around the world, only a handful of pets have tested positive for the original SARS-CoV-2—probably because no one is testing them. Infected pets appear to have symptoms ranging from mild to nonexistent, and infectious disease experts say companion animals are likely playing little, if any, role in spreading the coronavirus to people. The new variants might change that equation, says Eric Leroy, a virologist at the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development who specializes in zoonotic diseases. In one of the new studies, he and colleagues analyzed pets admitted to the cardiology unit of the Ralph Veterinary Referral Centre in the outskirts of London. The hospital had noticed a sharp uptick in the number of dogs and cats presenting with myocarditis: From December 2020 to February, the incidence of the condition jumped from 1.4% to 12.8%. That coincided with a surge of the B.1.1.7 variant in the United Kingdom. So the team looked at 11 pets: eight cats and three dogs. None of the animals had a previous history of heart disease, yet all had come down with symptoms ranging from lethargy and loss of appetite to rapid breathing and fainting. Lab tests revealed cardiac abnormalities, including irregular heartbeats and fluid in the lungs, all symptoms seen in human cases of COVID-19. Seven of the animals got polymerase chain reaction tests, and three came back positive for SARS-CoV-2—all with the B.1.1.7 variant, team reported yesterday on the preprint server bioRxiv. SARS-CoV-2 antibody tests on four of the other animals picked up evidence that two of them had been infected with the virus. Earlier this week, researchers at Texas A&M University detected the B.1.1.7 variant in a cat and a dog from the same home in the state’s Brazos county. The Texas owner was diagnosed with COVID-19, and owners of five of the 11 U.K. pets tested positive for SARS-CoV-2—all before their animals developed symptoms. The Texas pets showed no symptoms at the time they were tested, though they both began to sneeze several weeks later. All of the U.S. and U.K. animals have since recovered, though one of the U.K. cats relapsed and had to be euthanized. Leroy says it’s unclear whether B.1.1.7 is more transmissible than the original strain between humans and animals, or vice versa. It’s “impossible to say” that pets infected with B.1.1.7 might play a more serious role in the pandemic, he adds, but “this hypothesis has to be seriously raised.” Shelley Rankin, a microbiologist at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, points out that the researchers have shown only a correlation between B.1.1.7 infection and myocarditis, and that they didn’t rule out other causes for the condition. “There is no evidence pets were sick because of the virus,” she says. Weese agrees that neither the Texas nor U.K. findings should sound any alarms about pets endangering their owners. “The risk of them being a source of infection remains very low,” he says. “If my dog has it, he probably got it from me. And I’m much more likely to infect my family and neighbors before he does.” Still, he says scientists and veterinarians should do studies on what role, if any, SARS-CoV-2 and its variants play in myocarditis among pets. There is evidence that the virus can cause the condition in people, Weese notes, so it’s worth exploring in companion animals. “It might be real,” he says, “but there’s no reason for people to freak out right now.” Research cites posted in bioRxiv (March 18, 2021): https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.18.435945

|

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Infected rodents pose no immediate danger to humans, but the research suggests that mutations are helping the coronavirus expand its range of potential hosts. Bats, humans, monkeys, minks, big cats and big apes — the coronavirus can make a home in many different animals. But now the list of potential hosts has expanded to include mice, according to an unnerving new study. Infected rodents pose no immediate risk to people, even in cities like London and New York, where they are ubiquitous and unwelcome occupants of subway stations, basements and backyards. Still, the finding is worrying. Along with previous work, it suggests that new mutations are giving the virus the ability to replicate in a wider array of animal species, experts said. “The virus is changing, and unfortunately it’s changing pretty fast,” said Timothy Sheahan, a virologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was not involved in the new study. In the study, the researchers introduced the virus into the nasal passages of laboratory mice. The form of the virus first identified in Wuhan, China, cannot infect laboratory mice, nor can B.1.1.7, a variant that has been spreading across much of Europe, the researchers found. But B.1.351 and P1, the variants discovered in South Africa and Brazil, can replicate in rodents, said Dr. Xavier Montagutelli, a veterinarian and mouse geneticist at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, who led the study. The research, posted online earlier this month, has not yet been reviewed for publication in a scientific journal. The results indicate only that infection in mice is possible, Dr. Montagutelli said. Mice caught in the wild have not been found to be infected with the coronavirus, and so far, the virus does not seem to be able to jump from humans to mice, from mice to humans, or from mice to mice. “What our results emphasize is that it is necessary to regularly assess the range of species that the virus can infect, especially with the emergence of new variants,” Dr. Montagutelli said. The coronavirus is thought to have emerged from bats, with perhaps another animal acting as an intermediate host, and scientists worry that the virus may return to what they describe as an animal “reservoir.” Apart from potentially devastating those animal populations, a coronavirus spreading in another species may then acquire dangerous mutations, returning to humans in a form the current vaccines weren’t designed to fend off. Minks are the only animals known to be able to catch the coronavirus from humans and pass it back. In early November, Denmark culled 17 million farmed mink to prevent the virus from evolving into dangerous new variants in the animals. More recently, researchers found that B.1.1.7 infections in domesticated cats and dogs can cause the pets to develop heart problems similar to those seen in people with Covid-19. To establish a successful infection, the coronavirus must bind to a protein on the surface of animal cells, gain entry into the cells, and exploit their machinery to make copies of itself. The virus must also evade the immune system’s early attempts at thwarting the infection. Given all those requirements, it is “quite extraordinary” that the coronavirus can infect so many species, said Vincent Munster, a virologist at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. “Typically, viruses have a more curtailed host range.” Mice are a known reservoir for hantavirus, which causes a rare and deadly disease in people. Even though the coronavirus variants don’t seem to be able to jump from mice to people, there is potential for them to spread among rodents, evolve into new variants, and then infect people again, Dr. Munster said. The variants may also threaten endangered species like black-footed ferrets. “This virus seems to be able to surprise us more than anything else, or any other previous virus,” Dr. Munster said. “We have to err on the side of caution.” Dr. Sheahan said he was more concerned about transmission to people from farm animals and pets than from mice. “You’re not catching wild mice in your house and snuggling — getting all up in their face and sharing the same airspace, like maybe with your cat or your dog,” he said. “I’d be more worried about wild or domestic animals with which we have a more intimate relationship.” But he and other experts said the results emphasized the need to closely monitor the rapid changes in the virus. “It’s like a moving target — it’s crazy,” he added. “There’s nothing we can do about it, other than try and get people vaccinated really fast.” Preprint available in bioRxiv (March 18, 2021):

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...