Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

- The CDC on Monday ramped up its monkeypox alert to level 2 and encouraged people to “practice enhanced precautions” to stem the recent outbreak.

- The new guidance includes wearing face masks while traveling, as well as avoiding close contact with sick animals and people, especially those with skin lesions.

- As of Monday, 1,019 confirmed and suspected cases of monkeypox have so far been reported in 29 countries, according to the public health body.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has stepped up its monkeypox guidance, urging travelers to take extra precautions including wearing face masks as global cases of the virus surpass 1,000. The CDC ramped up its alert to a level 2 on Monday, encouraging people to “practice enhanced precautions” to stem the outbreak, which has spread to 29 nonendemic countries in the past month. The highest level alert — level 3 — would caution against nonessential travel. While the public health body said the risk to the general public remains low, the heightened alert encourages people to avoid close contact with sick people, including those with skin or genital lesions, as well as sick or dead animals. It also urges those displaying symptoms of the virus, such as an unexplained skin rash or lesions, to avoid contact with others and to reach out to their health-care provider for guidance. Monkeypox is a rare disease caused by infection with the monkeypox virus, with symptoms including rashes, fever, headaches, muscle ache, swelling and backpain. It is typically endemic to Central and West African countries, but the recent outbreak across North America, Europe and Australia has confounded health professionals and raised fears of community spread. As of Monday, 1,019 confirmed and suspected cases of monkeypox have been reported in 29 countries, according to the CDC. The U.K. has recorded the most cases by far, with 302 suspected and confirmed infections. It is followed by Spain with 198, Portugal with 153 and Canada with 80. Health experts have been searching for clues as to the source of the outbreak, which has historically been linked to travel from endemic countries. The World Health Organization’s technical lead for monkeypox said Wednesday that the virus could have been transmitting undetected within nonendemic countries for “weeks, months or possibly a couple of years.” U.S. detects two monkeypox strains Until recently, the current outbreak was thought to have derived from the West African strain of the virus, which produces less severe illness than other variants and has a 1% fatality rate. However, the CDC said Friday that at least two genetically distinct monkeypox variants are currently circulating in U.S., adding to health experts’ confusion. The U.S. has so far reported 30 cases of the virus in total. “While they’re similar to each other, their genetic analysis shows that they’re not linked to each other,” Jennifer McQuiston, deputy director of the CDC’s high consequence pathogens and pathology division, said of the two variants at a Friday press briefing. McQuiston said it is likely that the two strains stem from two different instances where the virus has spilled over from animals to humans in Africa, before spreading via person-to-person contact. Professor Eyal Leshem, infectious disease specialist at Sheba Medical Center in Israel, told CNBC on Monday that the spread of the virus to nonendemic countries was unsurprising given the frequency and ease of international travel, as well as the increased interaction between humans and animals. “Diseases that were locally spread are now able to make their way across countries and continents much more easily,” Leshem said. “Meanwhile, interaction between humans and animals has also amplified. Climate change has forced some animals into closer contact with humans, you will see more of these types of diseases,” he added. Though most cases of monkeypox are mild, typically resolving within two to four weeks, the U.S. said Monday that it has 36,000 doses of a suitable vaccine which it is sending to people who have had high-risk exposures to the virus. Some European countries, including the U.K. and Spain, have announced similar measures to stem the spread of the disease. Monkeypox is not considered a sexually transmitted disease, though the majority of cases so far have spread via sex, and particularly men who have sex with men, according to the CDC. Revised CDC Alert Level and Guidelines (June 2022): https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/alert/monkeypox

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Vaccines have slowed the death rate, but officials warn of worrying rises in some countries. The milestone comes amid warnings from health officials that cases and deaths in some places are rising for the first time in months. Nearly 250 million cases of the virus have been recorded worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates the pandemic's real global death toll could be two to three times higher than official records. In the US, more than 745,800 people have died, making it the country with the highest number of recorded deaths. It is followed by Brazil, with 607,824 recorded deaths, and India, with 458,437. But health experts believe these numbers are under reported, partly because of deaths at home and those in rural communities. It has taken the world longer to reach the latest one million deaths than the previous two. It took over 110 days to go from four million deaths to five million. That is compared to just under 90 days to rise from three million to four million. While vaccines have helped reduce the fatality rate, the WHO warned last week that the pandemic was "far from over". Its director general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus pointed to a rise in cases in Europe, where countries with low vaccination rates are seeing soaring infections and deaths. Last week, Russia recorded its highest number of daily cases and deaths since the start of the pandemic. Russia accounts for 10% of the last million deaths recorded globally. Bulgaria and Romania have some of the world's worst Covid mortality rates, and their hospitals are struggling to cope. They have the two lowest vaccine rates in the European Union. More than seven billion vaccine doses have been administered worldwide, but there is a gap between rich and poor nations. Only 3.6% of people in low income countries have been vaccinated, according to Oxford University's Our World in Data. Dr Tedros said that if the vaccine doses had been distributed fairly, "we would have reached our 40% target in every country by now". "The pandemic persists in large part because inequitable access to tools persists," he said. Vaccines have allowed many countries to gradually open up, with most of the world now easing restrictions. On Monday, Australia reopened its borders for the first time in 19 months. But China, where the pandemic first emerged, is still perusing a zero-Covid strategy, where even one infection can result in a strict lockdown and mass testing. A country's death toll is based on daily reports from the nation's health authorities, but the numbers may not fully reflect the true toll in many countries. Not all countries record coronavirus deaths in the same way, meaning it is difficult to compare their death rates. Comparing how different countries have suffered during the Covid pandemic is difficult. Total number of deaths is one way, but this number masks some crucial context. How much testing individual countries carry out will have a bearing on their death figures. Very few deaths have occurred in Africa, for example, compared to other continents and this is likely to be one factor. Deaths from Covid can also be measured in different ways - as a proportion of the population (Bulgaria fares worst) or as a proportion of people showing symptoms (Mexico fares worst). And the healthcare systems in different countries as well as the average age of the population will also have an impact - the older the people the more vulnerable they are to the virus. Vaccinations against Covid have made a huge difference to the number of people dying in the past six months - but not all countries have had equal access to shots which protect against the virus. That means there will be more deaths to come - but Covid is not the only health problem the world has to worry about. It's worth remembering that each year more than nine million people die from cancer and nearly the same number from heart disease.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Over the past 10 months, the virus has taken more lives than H.I.V., malaria, influenza and cholera. And as it sows destruction in daily life around the globe, it is still growing quickly. More than H.I.V. More than dysentery. More than malaria, influenza, cholera and measles — combined. In the 10 months since a mysterious pneumonia began striking residents of Wuhan, China, Covid-19 has killed more than one million people worldwide as of Monday — an agonizing toll compiled from official counts, yet one that far understates how many have really died. It may already have overtaken tuberculosis and hepatitis as the world’s deadliest infectious disease, and unlike all the other contenders, it is still growing fast. Like nothing seen in more than a century, the coronavirus has infiltrated every populated patch of the globe, sowing terror and poverty, infecting millions of people in some nations and paralyzing entire economies. But as attention focuses on the devastation caused by halting a large part of the world’s commercial, educational and social life, it is all too easy to lose sight of the most direct human cost More than a million people — parents, children, siblings, friends, neighbors, colleagues, teachers, classmates — all gone, suddenly, prematurely. Those who survive Covid-19 are laid low for weeks or even months before recovering, and many have lingering ill effects whose severity and duration remain unclear. Yet much of the suffering could have been avoided — one of the most heartbreaking aspects of all “This is a very serious global event, and a lot of people were going to get sick and many of them were going to die, but it did not need to be nearly this bad,” said Tom Inglesby, the director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, which aims to protect people’s health from epidemics and disasters. Places like China, Germany, South Korea and New Zealand have shown that it is possible to slow the pandemic enough to limit infections and deaths while still reopening businesses and schools. But that requires a combination of elements that may be beyond the reach of poorer countries and that even ones like the United States have not been able to muster: wide-scale testing, contact tracing, quarantining, social distancing, mask wearing, providing protective gear, developing a clear and consistent strategy, and being willing to shut things down in a hurry when trouble arises. No one or two or three factors are the key. “It’s all an ecosystem. It all works together,” said Martha Nelson, a scientist at the National Institutes of Health who specializes in epidemics and viral genetics, and who studies Covid-19. It comes down to resources, vigilance, political will and having almost everyone take the threat seriously — conditions harder to attain when the disease is politicized, when governments react slowly or inconsistently, and when each state or region goes its own way, advisable or not. “It’s one thing to have all the technical capabilities, but if our leaders undermine science, minimize the epidemic or falsely reassure people, we put everything else at risk,” Dr. Inglesby said. Time and again, experts say, governments reacted too slowly, waiting until their own countries or regions were under siege, either dismissing the threat or seeing it as China’s problem, or Asia’s, or Italy’s, or Europe’s, or New York’s. Thomas R. Frieden, a former head of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said that a major failing had been in governments’ communication with the public, nowhere more so than in the United States “You have standard principles of risk communication: Be first, be right, be credible, be empathetic,” he said. “If you tried to violate those principles more than the Trump administration has, I don’t think you could.” The world now knows how to bend the curve of the pandemic — not to eliminate risk, but to keep it to a manageable level — and there have been surprises along the way. Masks turned out to be more helpful than Western experts had predicted. Social distancing on an unheard-of scale has been more feasible and effective than anticipated. The difference in danger between an outdoor gathering and an indoor one is greater than expected...

|

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

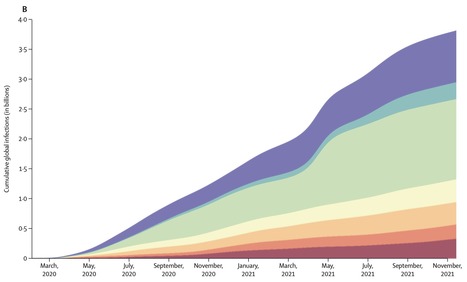

COVID-19 has already had a staggering impact on the world up to the beginning of the omicron (B.1.1.529) wave, with over 40% of the global population infected at least once by Nov 14, 2021. The vast differences in cumulative proportion of the population infected across locations could help policy makers identify the transmission-prevention strategies that have been most effective, as well as the populations at greatest risk for future infection. This information might also be useful for targeted transmission-prevention interventions, including vaccine prioritisation. Background Timely, accurate, and comprehensive estimates of SARS-CoV-2 daily infection rates, cumulative infections, the proportion of the population that has been infected at least once, and the effective reproductive number (Reffective) are essential for understanding the determinants of past infection, current transmission patterns, and a population's susceptibility to future infection with the same variant. Although several studies have estimated cumulative SARS-CoV-2 infections in select locations at specific points in time, all of these analyses have relied on biased data inputs that were not adequately corrected for. In this study, we aimed to provide a novel approach to estimating past SARS-CoV-2 daily infections, cumulative infections, and the proportion of the population infected, for 190 countries and territories from the start of the pandemic to Nov 14, 2021. This approach combines data from reported cases, reported deaths, excess deaths attributable to COVID-19, hospitalisations, and seroprevalence surveys to produce more robust estimates that minimise constituent biases. Methods We produced a comprehensive set of global and location-specific estimates of daily and cumulative SARS-CoV-2 infections through Nov 14, 2021, using data largely from Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD, USA) and national databases for reported cases, hospital admissions, and reported deaths, as well as seroprevalence surveys identified through previous reviews, SeroTracker, and governmental organisations. We corrected these data for known biases such as lags in reporting, accounted for under-reporting of deaths by use of a statistical model of the proportion of excess mortality attributable to SARS-CoV-2, and adjusted seroprevalence surveys for waning antibody sensitivity, vaccinations, and reinfection from SARS-CoV-2 escape variants. We then created an empirical database of infection–detection ratios (IDRs), infection–hospitalisation ratios (IHRs), and infection–fatality ratios (IFRs). To estimate a complete time series for each location, we developed statistical models to predict the IDR, IHR, and IFR by location and day, testing a set of predictors justified through published systematic reviews. Next, we combined three series of estimates of daily infections (cases divided by IDR, hospitalisations divided by IHR, and deaths divided by IFR), into a more robust estimate of daily infections. We then used daily infections to estimate cumulative infections and the cumulative proportion of the population with one or more infections, and we then calculated posterior estimates of cumulative IDR, IHR, and IFR using cumulative infections and the corrected data on reported cases, hospitalisations, and deaths. Finally, we converted daily infections into a historical time series of Reffective by location and day based on assumptions of duration from infection to infectiousness and time an individual spent being infectious. For each of these quantities, we estimated a distribution based on an ensemble framework that captured uncertainty in data sources, model design, and parameter assumptions. Findings Global daily SARS-CoV-2 infections fluctuated between 3 million and 17 million new infections per day between April, 2020, and October, 2021, peaking in mid-April, 2021, primarily as a result of surges in India. Between the start of the pandemic and Nov 14, 2021, there were an estimated 3·80 billion (95% uncertainty interval 3·44–4·08) total SARS-CoV-2 infections and reinfections combined, and an estimated 3·39 billion (3·08–3·63) individuals, or 43·9% (39·9–46·9) of the global population, had been infected one or more times. 1·34 billion (1·20–1·49) of these infections occurred in south Asia, the highest among the seven super-regions, although the sub-Saharan Africa super-region had the highest infection rate (79·3 per 100 population [69·0–86·4]). The high-income super-region had the fewest infections (239 million [226–252]), and southeast Asia, east Asia, and Oceania had the lowest infection rate (13·0 per 100 population [8·4–17·7]). The cumulative proportion of the population ever infected varied greatly between countries and territories, with rates higher than 70% in 40 countries and lower than 20% in 39 countries. There was no discernible relationship between Reffective and total immunity, and even at total immunity levels of 80%, we observed no indication of an abrupt drop in Reffective, indicating that there is not a clear herd immunity threshold observed in the data. Published in The Lancet (April 8, 2022):

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

Nations short of vaccine should get first doses to curb the pandemic, researchers say. Israel has announced plans to begin giving booster shots to older adults next week, in the hope of increasing their protection against COVID-19 — and a number of other wealthy countries are considering the same. But global-health researchers warn that this strategy could set back efforts to end the pandemic. Each booster, they say, represents a vaccine dose that could instead go to low- and middle-income countries, where most citizens have no protection at all, and where dangerous coronavirus variants could emerge as cases surge. Data do not yet show that extra doses are needed to save lives, researchers say, except perhaps for people with compromised immune systems, who might fail to generate much of an antibody response to the initial COVID-19 shots. An internal analysis from the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that if the 11 rich countries that are either rolling out boosters or considering it this year were to give the shots to everyone over 50 years old, they would use up roughly 440 million doses of the global supply. If all high-income and upper-middle-income nations were to do the same, the estimate doubles. The WHO maintains that these shots would be more useful for curbing the pandemic if they were sent to low- and lower-middle-income countries, where more than 85% of people — some 3.5 billion — haven’t had a single jab. “The priority now must be to vaccinate those who have received no doses,” said WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus at a briefing on 12 July. All of the COVID-19 vaccines authorized by most high-income countries reduce a person’s risk of hospitalization and death by more than 90%. Scientists don’t yet know how much more a booster — typically an extra jab of an mRNA-based vaccine on top of the standard doses — would protect the average person, although data are beginning to trickle in. The effects of not receiving any vaccine are more certain. On the African continent, where only 2% of people have been vaccinated, COVID-19 rates are escalating, with fatality rates higher than the global average. Without vaccines, researchers say, the best tools for slowing the spread of infections are interventions such as closing businesses and schools, which can have devastating economic consequences. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that 95 million people were pushed into extreme poverty during the pandemic last year, and numbers are rising. On 27 July, the organization reported a widening wealth gap between rich countries and the rest of the world. What’s more, evolutionary biologists say that countries with low vaccination coverage are ripe for the emergence of further dangerous variants of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. “Right now, our destiny relies on distributing vaccines so that continued transmission doesn’t occur,” says Nahid Bhadelia, director of the Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases Policy and Research at Boston University in Massachusetts. “We don’t want to be chasing our tail in terms of new variants.” Contemplating boosters Israel is not alone in considering boosters for older people. Spurred partly by data1 suggesting that antibody levels wane over time, the United Kingdom has drawn up plans — but not given final approval — for a booster programme to begin in September for older people, front-line health workers and others at high risk of COVID-19. In early July, the US government decided against boosters for the time being, but said it was prepared to roll them out when science demonstrated a need. Last week, the United States purchased another 200 million mRNA vaccines made by pharmaceutical firm Pfizer, based in New York City, and biotechnology firm BioNTech, based in Mainz, Germany, that might be used for booster shots if studies show they are necessary. The United States and other nations are hesitating because current COVID-19 vaccines still protect people, despite uncertainty about how long their effects will last. This week, a not-yet peer-reviewed report from Pfizer2 found that its vaccine’s efficacy rate against symptomatic COVID-19 fell from 96% for the two months after the usual two doses to 84% six months later. But its efficacy against severe disease remained high, at 97%. Decisions on boosters might also be influenced by the rise of the Delta variant in many parts of the world, and the possibility that vaccinated people could transmit it to others if they become infected. In theory, further reducing the risk of infection for vaccinated people diminishes the possibility of Delta's spread. The variant was first reported in India in late 2020, but remained relatively rare until March, when a surge occurred. Few people in the country had been vaccinated at the time, allowing the virus to spread in India and beyond. A similar scenario might play out again in an area with low vaccination coverage and a lot of COVID-19. A new variant could arise that is more transmissible or deadlier than Delta, or that allows the virus to escape — at least to some extent — immunity gained from vaccination or a previous infection, says Katrina Lythgoe, an evolutionary biologist at the Big Data Institute at the University of Oxford, UK. “Making predictions is really hard,” she adds, but it’s safe to say that in places with more infections, there are more viruses replicating and therefore more opportunities for variants to evolve....

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

|

New cases of the novel coronavirus are rising faster than ever worldwide, at a rate of more than 100,000 a day over a seven-day average. In April, new cases never topped 100,000 in one day, but since May 21, there have only been less than 100,000 on five days, according to data from Johns Hopkins University. Newly reported cases reached a high of 130,400 on June 3. The increase in case rates may be partially explained by increases in testing capacity, but there's still not enough testing to capture an accurate picture in many countries. Different nations' epidemics have followed different trajectories. The number of new cases has slowed in many of the countries that were hit hard earlier on in the pandemic, including China, the US, UK, Italy, Spain and France. But many countries, particularly in South America, the Middle East and Africa, the rate of transmission still appears to be accelerating, according to a CNN analysis of Johns Hopkins University data. In Libya, Iraq, Uganda, Mozambique and Haiti, the data shows the number of known cases is doubling every week. In Brazil, India, Chile, Colombia and South Africa, cases are doubling every two weeks. The Americas continues to account for the most cases. For several weeks, the number of cases reported each day in the Americas has been more than the rest of the world put together," said World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus on Wednesday. "We are especially worried about Central and South America, where many countries are witnessing accelerating epidemics." Dr. Mike Ryan, WHO executive director of Health Emergencies Program, said he did not think Central and South America had reached their peak in transmission. The share of global deaths is also still rising in South America and the Caribbean. Brazil recorded more than 30,000 new cases on Thursday, bringing it to almost 615,000 in total, along with 1,473 new deaths, taking its total fatalities to more than 34,000....

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...